Chapter 1

MONSTER UNDER THE BEDROCK

Luma was first to enter the jaws of this armageddon.

She had strayed from her pack, as all mortals make the mistake of doing eventually. A lone elf stumbling through the forest on a tall drink of nervous energy and abandonment issues, eyes flooded and blurring her path. The girl shuffled along at the pace of her defeated heart, her boots unready to avoid even the shallowest pitfall, and for these weaknesses she soon found herself deep below the forest floor, tumbling ceaselessly through cavern and burrow, just as battered by root and rock as she had already been by love and lament.

Unlike a typical fall, it did not end at the ground, since that was where it began. Instead it wasted a quarter-hour in pursuit of a depth to match her despair, and only ended when it found us, as we were, in the solitude and silence of a dirt room three miles beneath the world stage. Luma slid into our den on an avalanche of gravel, a pitiful thing lost in every way worth mentioning.

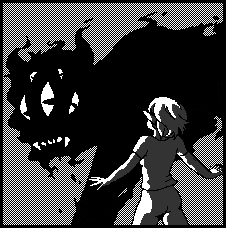

She might have simply stayed there and treated it as a grave, if she thought that was an option, for such an idea at least matched her bitterness. But she righted herself upon hearing the growl.

It was the unmistakable growl of a stomach roused from hibernation, born of a hunger so apocalyptic that dust and debris freed themselves from the ceiling upon hearing its demands. Not ten feet from her feeble elven limbs slept a beast of pure, unrecognizable darkness. An ancient, royal monstrosity designed for infinite brutality and incomparable destruction. Beneath the surface of its bulk shimmered a legion of souls and stars, long ago swallowed into a library of life stories converted down to histories. When it opened its eyes, it did not stop at two, but cascaded into a multitude, all of which opened upon her alone.

We have high expectations. We always expect screams and howls, desperate scrambling, and for mortals to bargain and plead with both us and whatever gods are known to them. Rising up for the very first time in that world, we gazed down at the puny elf and listened to her total silence.

Luma gave us only a fascinated stare, and we in turn also did the very last thing she expected from us, and spoke.

We said, “Usually the first is already dead...”

And when she did not panic, we elaborated. “In all other worlds, reduced to only a sack of broken bones and torn flesh by the time they ragdoll into our den.”

Sometimes it takes a moment for our voice to drip through a mortal skull, and light up a brain like fire-tar upon leaves. To this one, it was only a moment before she started taking slow steps towards us.

We asked, “Where is your fear, young fool?” And we let the girl reach out, getting a tiny fistful of ether to wonder at. “Do the mortals of this world not fear what they do not comprehend?”

We stamped her to the dirt, claws wringing the spongy flesh of her frame. Standing upon her, we drooled speech into her mind. “We are a Devourer. We are not part of your game, nor do we have a part to play on your stage. We are the curtain that falls over it; the storm that cancels the sport. Our hide is as invulnerable to might and magic as the night sky is to a javelin, and our bite empties horizons before we’re even grown. From here, all you know will be stolen over our edge with you. Even the rocks and rivers of your homeland will vanish into us.”

This was far more than we had said in other worlds, but Luma listened to it all with a dutiful and generous attention — without even inching for a dagger or eying for an exit. The girl held within herself a theatrical soul, and thought that our many words betrayed the same in us. She would have loved to volley jokes and questions, and make an evening of indulging us, as was her custom, but did not think it possible.

That changed when we responded to her very thoughts. “You think because the beast has language, they are a storyteller? As starved for a good listener as they are for meat and marrow?”

The girl lit up, already experienced in preparing her words to be telepathically read. She thought, Of course! Who is not captivated by a captive audience?

Luma blinked, grinned, and waited.

We blinked all across our body, and said, “You guess well. But we have already told all our stories to the gods that charged us with taking them. A new world waits on a platter. Our undeniable hunger remembers itself, and your soul is thick with the scent of sugar and dough.”

We ran a suffocating tongue of endless stars over her face, which did not startle as it should. And we learned from it.

“A bard, are you? As talented as you are sweet. But... deeply burned inside. A silenced bard, and bitter about it. You were as unlucky above the surface as you were to fall through it.”

Luma pouted. Something that must have worked often on others, as her face was made for it above all else. And while it bounced off her killer she thought, Why are you hidden in a hole? Too much beauty to bury.

“We are a precaution.” She got a story that no god would ever ask to be gathered, and no mortal was meant to know. “Worlds left alone outlive the few early eras that resonate well with gods, and spoil. Cheap worlds, half-baked and left to boil over, forget to war themselves into the ground. When their people have multiplied across the surface, and their cracks begin to show, odds demand that a stray such as yourself falls into the failsafe seeded deep below the crust, and triggers a backup armageddon. A Devourer cannot be fought even with infinite valiance, and so our feast is an unsatisfying conclusion that only we enjoy, but such is the fate of all creations that have gone off script.”

Her whole face squinted in thought, but then decided right away. What is the point of a world if it has to end?

A very elven question, though not a common one. “Is this world so young that the elves do not yet know death?” A bad sign. “New worlds are not meant for us. But we will act in our nature. If the rest of this world is still anything like you, its end will be swift.”

Luma, a being of infinite ambition, got up, rolled up one sleeve, and offered her arm to us — foolish kindness sparkling behind her eyes. If you need to chew on the defeated, I have the time!

It was not new to have bright young girls offered to us, typically strewn in garlands and perfumes and chastity. And while they always bore this inane hope their flesh could sate the void itself, very few ever believed they would survive. Fewer still idled their thoughts on us, rather than their peers. Luma nudged her arm forward and — as if we couldn’t see it a dozen times over — she stealthily placed her other hand atop us, and ruffled the void, petting our library of dead worlds and infinite ink.

“You are sweeter than the grandest confectionery.” We growled a pure and tactile wave of psychic terror that shook everything except the girl’s nerves. “All we care to know now, is if the rest of this world is still naive and ripe, like you.”

Before she could form another packet of thought, we told her, “No need. We take our answers,” and bit into her head.

Chapter 2

THE UNSPOKEN IRONY OF A MUTED BARD

Deep in that mess, beyond several surprises, past oceans of yearning, and beneath the crushing undertones of toffee and butter, waited our unwelcome answer.

For while you yourself have likely read the grandest of worlds and histories, and become familiar with the major creative gods and their works, do not let such thin exposure give you an illusion as to the whole of it. Any Devourer can testify to you (having been repeatedly seeded into whatever haphazard world) the regularity with which we find ourselves chewing upon the most pitiful creations of pantheonic habit.

Much of creation is not, in the sense that you understand it, creative. The bulk of worlds are created in chase, out of a god’s worry they must prove themselves to belong in the same pantheon as their elders, a habit that has left behind countless worlds without anything special to them. Many mortals have asked how the gods create something from nothing, but they are missing the face of it. They think the addition of mass and matter and bloodshed means a world no longer has nothing to it.

You may think that to say this is to risk the ire of our own god. But he is referred to here, candidly, and lowercase, for it is evident that even if he did not entirely forget about the project, he at least lost interest halfway through its first century, and quite possibly lost the project itself. The reason we are certain he will not return to read this world’s history is because he did not return to right it, either. Something which, being quite outside of mortal time, if he was ever going to do would have already been done. It is our opinion that this world resides nowhere grander than a cosmic storage bin, where it will likely remain for an eternity hence.

Now that you know this, the author would like to make it clear, here in the opening, that this very history of the world is being written entirely in the spirit of pure and unmitigated spite.

So it is that this account will not cover the larger histories, or even thin the timeline down to major events. We will abridge, editorialize, contextualize, digress, commentate, and forgo both the glossary and appendix in the way we have always envied of fiction authors we consumed. And we very much wish to recount the close of the eighth century, for that is when the ragged clockwork of this world finally gave up the act, opened at the seams, and fell to pieces.

As it is a rotted world that was served to us, so too will our work be rotten in its own way, and fit only for mortals, written in the flattened dimensionality of their tongue, with that tedious way it must be bitten off in sequence rather than swallowed whole. Consider it a cypher that no god as lazy as ours would bother to decrypt. Should any other divinity peer into this capsule and find so disobedient a report, let them need to squint.

✦ ✦ ✦

According to the digested wisdoms of innumerable authors, mortals prefer their stories centered around the most relatable characters involved, even if they must be fabricated for the role. Luckily we are in need of no such deceit, and can proceed with the very same Luma. She was, at the time we choose to begin her story, listless in mind, ravenous in hunger, soon to wake from a deep hibernation, and would become instrumental in ending the grand design itself.

You might spy the pattern, and think to yourself that this list does not sound relatable to anyone but a Devourer, and so Luma has only been protagonized in a bout of favoritism and recency bias. But you would also be welcome to make your own visit to this world, and deliver to us your critique in the flesh, along with your flesh. While it is bothering you, let us note that a bard is very closely related to a storyteller, except that a bard works in song rather than ink. What a coincidence then, that Luma was entirely muted, and so happened to only speak in ink anyway.

The irony of her handicap was not lost on as many as she would’ve wished. This was the fault of her strumweave, and her fault to still carry the thing, but having had no say in parting with her voice she refused to part with what was left, even if that meant strangers asking her for song, or verse, or worse: explanation. All things she wished not to talk about, and couldn’t, anyway.

Which wasn’t to her nature. Our Luma was the type to talk often, and talk an ear off, and not fond of her new nature. So much would she not have chosen it that she chose instead to go on a most tedious quest, and spent seven years away from the warm beds of friends, on paths of dirt and stone and certainly not of soul, traveling wide and wildly in an attempt to free herself.

This was why, after exhausting her options in another unremarkable city, Luma chose to wait out her evening in the worst tavern she could think to visit, where the seats were all taken twice and the performers felt compelled to make it impossible to hear anything else. The perfect opposite to silence, for it muted everyone around her and made conversation almost as difficult for others as it was for her.

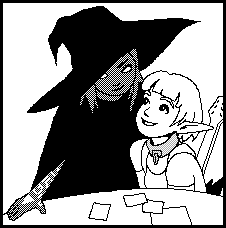

Yet through those defenses came a young mage carrying her own stool, who dropped in beside Luma, put an elbow to her table, chin in hand, and smiled at her wordlessly. An ominous entrance for which Luma returned a blank pause, having completely atrophied any instinct to take the initiative when met. But it turned out that this stand-off was a quick-draw, because the instant Luma flinched first, the girl whipped out a note, pre-printed on a card.

It read, I am glad to see you escaped your captivity.

A handful of days prior, when Luma was in a dead sleep atop some particularly drab studies, drooling dangerously close to a valuable historic leatherbound and sitting in the trajectory of a roaming librarian, a passing student had kicked her chair leg on their way by, startling her awake just in time to instinctively wipe her mouth and look busy, or at least cognizant, and narrowly evade getting ousted or banned from the university library.

Luma pointed in recognition, right as this mage added another note, reading, I cannot imagine a worse place to be shackled at night.

Then without waiting, she placed under it, Surely there are better beds to sleep in.

With a smirk.

Not all mages thought they were clever — the amount was really only slightly inflated from normal — but almost all mages acted like they thought they were clever, because that had been the style for all of history. This one was the former, and right about it, and clever enough to write to Luma, which even in the clamor of that tavern was as unexpected as it was appreciated.

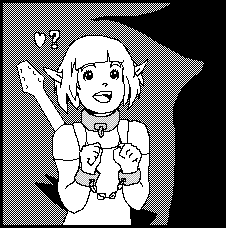

In reaction to this, Luma — who believed herself to be an elf of great company and bardish wit — immediately and literally choked on her words, even though she didn’t have any, and possibly more because she couldn’t think of any.

Watching her once-powerful social engine fail to start stranded Luma in a desert of panic. Such an unforced error made her look unsocialized, maladjusted, or a wallflower, and these were all the worst possible things for an elf to be, especially in comparison to human company. It was one thing to forgo charming a clerk or stableboy, but quite another to be accosted by humorous wordplay and return a blank. So somewhere in between coughs she undertook a desperate need to prove that she had not dropped her charm somewhere along the many empty roads of recent years. She grabbed stationary and immediately wrote upon it, in the way that she remembered flirting to work, Sleep is rarely my plan, even in bed.

The mage smirked anew and instantly played a card reading, That would explain why it sneaks up on you so.

And Luma laughed. An ancient ability that she was born with but had forgotten about. In the din of that tavern she was able to forget it was silenced, and felt it the same as she used to. Except in this instance she laughed right in the girl’s face and forgot to refine it into a signal of anything but shock. Only remembering with a late step to cut it short for modesty, and shrink back to her own stool and the respectful mannerisms of the not-entirely desperate.

She was being charmed, and realizing it set off a warning klaxon in her head, this time not out of competitive indignity but because of the danger it presented. So Luma collected herself, and in accordance with protocol she reminded her mental faculties that they were not to — under any circumstances — fall in love. That may sound like an overreaction to you, but there was precedent.

Luma found love too easily. Luma was the type to find love under a rock. And if she let herself, she would spiral into assorted affairs in nearly any town the wind took her to, and never get anything done. It was a keen awareness of this lethal slope underneath her — her love of people which would consume her if she slipped for more than a night — that kept her head in books, studying from wake until the words blurred and her eyes mutinied between them. To manage the feat, Luma had left friends behind, and had since blocked new ones from emerging. A strategy she was not great at, and one which she herself was the greatest threat to. Most elves already found love much easier than humans did, due to the guidance of a small ancillary gland nestled amongst the intestines, of which Luma’s was abnormally sized and particularly overactive, currently steering her unconscious mind on track for a rich downwards spiral into this stranger’s eyes.

She needed to flirt no further, and so gathered everything she knew about wit and prose together for one go, threw it out the window and shuttered. She looked anywhere that was less distracting than the girl, took to her parchment and let flow the witless and casual pleasantries of the mundane. The weather and the crowds. How the nearby school threatened to swallow this town. How Luma blended in while the mage stood out. And soon enough she had written, Where did you find eyes inside which any bard could die?

There are good reasons why we begin Luma’s story not at the time of her muting but rather at this idle meeting, which demand that we explain the mage effectively.

It is imperative that you understand how incredibly sour she was to the tongue. It is true that she had a tanginess that dulled that, but it came mostly in the aftertaste. Attempting to consume her was the equivalent of throating a gaggle of lemons laced with razors, as she was not the type to go down without getting to rub acid in your wounds for the spite of it. Worth experiencing, still, and there are many other ways in which we can relate to her. For instance, she had approached our sweet Luma with an appetite, ready to bite, carrying an intent to get the bard in her mouth and enjoy her squirm.

If that does not clarify it enough, know that she was two things on the surface: entirely obfuscated by a cloak of vantablack thread, and studying Luma with eyes of pure gold. Not the color, but the metal — solid, glossy, and desireable. They held a magic that made them more reflective than mundane riches, not unlike the eyes of a cat — especially the type to bestow ill luck upon a crossed path.

Her unnatural fabrics reflected nothing but prying eyes, dragging any wandering light to an early grave, and her whole ensemble was entirely themed around this voidish near-illusion. Even the girl herself flirted with the edge of what could be considered natural, her body seeming achromatic in one moment, then suddenly remembering to include browns in its palette the next.

It was an intimidating look, or predatory. Most people existed by happenstance and learned to make it work. Because of this, many also experienced an alien sensation when meeting, in person, someone so well-funded and prepared that they had the look of being purpose-built for life. It was only by having stared at her once before that Luma evaded staring dumbly then. The mage stared at her the opposite way.

She saw through her, read between her lines, took Luma’s page of stumbling confusion and simply turned it face down. A merciful reset, beginning with, I so love your fashion.

Luma found some comfort in writing, Thank you. I hate it more than anything in this world.

For what it was that sealed Luma’s voice was a steel around her neck, and no metaphor. A collar too tall and wide to comfortably hide, and she didn’t make the attempt, anyway. Her heart still harbored a small fantasy that one day a stray pedestrian would recognize it on sight, happen to know of its rare magic, and end her quest right there, getting a thousand highly pitched thanks for their aid.

The girl placed, You must tell me where you got it. And this got a dark scowl out of the cutest elf for miles.

Somewhere between the drinking and the hangover. A sorry truth that had left her with no leads to follow.

It looks expensive. Even custom-made. Did you get it for free?

No. Luma set like the sun. It cost me everything. I paid with my very life.

But this didn’t faze the girl, who grinned the most perfect teeth under the sun, handing out, And yet you live?

Yes. Luma couldn’t write no, but couldn’t write the thousand pages of complex lamentations she had been refusing to process during her fruitless quest, either. So she settled for, That, and a pause, seems to be how it works.

The mage might have looked at her, or inside her, or through her — it couldn’t be known. But she saw something in Luma, and rather than attempt the poetry necessary, she let it be reduced to basic words. I see much life in you yet. And the collar fits you well. Then, Well enough to wear every day, I would say. I would not be so shy.

Shy!

Luma puffed, unwittingly, as if she might float right away from this, and tried to hide how insecure she was about her own insecurity. She held her hand steady, but still wrote the biting words, You like it? Take it. I insist.

The mage put hands on herself, as if complimented. It would not fit me. She might have laughed, the way she grinned. But I can never resist a girl in chains.

Once that card was placed down, the mage then pretended to have forgotten the put word helping in the middle, and used Luma’s quill to scribble it in.

It was not uncommon for various mages to puff up at the chance to take their shots at Luma’s puzzle. Something that appealed more to the young and the apprentices than to the masters, who learned long ago that they could charge half a fortune simply to tell a pitiful bard that they couldn’t help. The latter made her feel played, while the former made her feel played in the way that a lottery is, which was not much better. In the beginning Luma had been more willing to be taken on their rides, for they gave her the only hope she ever had that wasn’t born of necessity, but that edge had worn away long ago.

This mage, by contrast, touched her collar once and the very next words played from her deck were, This cannot be unlocked. It is impossible.

Which would have been refreshing were it not terrifying, and quick to send Luma dissociating. Normally, she would write out the practiced and routine thanks that pleasantries demanded follow an attempt at charity, but this encounter left her sitting lost in herself.

Do not despair far. The girl played a full hand. What is magic if not the art of doing the impossible? I am sure there was a time it seemed impossible to shut you up. Then a mage of poor taste came along, scowled at your voice, and set about making it happen.

Luma wrote, I have not seen this. I have spent unknown years now on the roads of this kingdom, in its every library and school. If time and trial made the impossible into the possible, I would not be here. I would not be this. And even this slight vent was an indulgence.

True. But Pedesyn is not like the elven homeland, Luma. Its libraries are unlikely to hold clues for you. Compromised magics, all of them. I will tell you this much: magic is a game of secrets. I can tell you this because it is an open secret. But all the best secrets are the ones that have been kept, especially from you. They are all — like you — chained up in obscurity, where only a rare few have opportunity to know of their names and potential.

This was one of the many things that Luma knew, but couldn’t have told you, or herself.

She had acted on it in the beginning, before it was inactionable and therefore necessary to forget about. Luma wrote, I have been to every master that would see me!

And after a lingering realization dripped through her, she waved the girl’s response away and asked, You know my name? For Luma had given her name to no one in that city, nevermind in that conversation, and yet it had been so casually placed in there, professionally embossed on a card. As if to prove a point about secrets and who had them.

I know the first one, as you carry it in your pocket. The mage held up a more familiar note, the one Luma kept ready for a convenient greeting, then reached over and tucked it back from whence it was picked, patting Luma’s side neatly. But it is only the one. I expect such as you to have many more.

Luma pressed her lips and wrote, Well I don’t carry a name as recognized as yours.

You know my name?

I know the last one! Everyone did, on sight. For while House Menemor didn’t have its own colors, the complete absence of them worked the same.

Every other house had been founded in the first century, back when the ground was raw and the world was still deciding not to make the grass purple. House Menemor emerged from the dark sometime between the sixth and seventh, basically yesterday by comparison, and this had all the ancient and official houses watching it closely, practically baring their teeth.

Which wasn’t unearned, either. Menemor were known as a house of shadow mages, for their presence was there one moment and gone the next, impossible to find, besiege, sabotage, or tax. But this did not give it as light a touch as you might think. Unofficial as it was, the time when it was a joke to call it a real mage house was a narrow few decades. Even Luma herself did then carry one of its products upon her. The one that carried the rest of her stuff, actually: the lightweight bag of pocketed dimension that had become standard across Pedesyn, which was the reason for which this Viccipiter’s eyes were a solid gold rather than the silver of its founders.

She was handed, Then I will trade you. Along with a card introducing, Viccipiter Entraste Sandid-Opponano Pontanious Casel et Menemor.

Twenty-two syllables was modest. Mages had complex names to fit their identities as masters of the complex arts, preferring them to sound more like incantations when spoken in full, presumably to keep their acquaintances on their toes and feeling like someone had just summoned a great serpent or cursed them with bad luck in love and hairline.

Viccipiter slid over a card that was Luma’s first name with a conspicuous blank thereafter. And our elf wrote upon it so that it then said, Luma Null.

Which wasn’t much different from saying nothing at all. Null was the family name of those who had no family, which did not, unfortunately, make them any sort of family of their own. Luma had once come from something like a family, a long time ago and across a great ocean, where the elves had a continent to themselves. But elven familial trees were eye-glossing contortions, so lost in their endless relations that no one ever considered naming their offspring by any such chaos. The necessity of secondary names was typically a surprise to newly-arriving elves, and those who made the journey alone had nothing to reference.

Viccipiter held it up to herself as if she had eyes to read it. And with her offhand she put down, This trade was a cheat. Her eyelids limited her gold to a squint. But as she turned it over in her hand, her face changed to that of equal mischief, almost as if Null seemed a preferable answer to her. (It was also likely the most welcome answer to an abductor.) And when she gave it back to Luma it had been changed to read, You are a mischievous thing. But we have mischief in common. I will trade you again. And she leapt from her seat, taking an unexpected extra step, having forgotten her intake so far that evening.

There was a minor flash every time the mage’s hands exited their cloak. Each was thickly covered in elegant tessellations of golden runes that looked so magically intense as to be questionably out of place here, trying to pick up a random musician after drinks (rather than busily sealing some great eternal demon underneath a monastery somewhere — or summoning it). Had she not been betraying eagerness with her smile and lean, Luma would have hesitated thrice to suspect such an appearance to harbor a flirt, but there was a charm to her confidence that threatened to be just as intoxicating as the girl was visibly intoxicated.

The Menemor splayed her deck and made Luma pick from it. She was not prepared for the extent to which Luma was Luma, and therefore ducked to see their undersides, rewarded by the knowledge that they were, all of them, blank. This underhanded move got a smirk, and then Luma also picked several cards at once. Each one said, Take my side for this night and I will take you anywhere in the world that you can name.

Anywhere? Luma was hit by the sudden realization that she was but a simple invitation away from a place of either many or the most secrets, and felt luck brush her neck for the first time in years. So she wrote, I will not cheat you, I promise!

Yes you will, but that is the deal. Viccipiter tapped the words, Go ahead.

So Luma got a bit giddy, and let herself shudder before writing, Take me into the shadow house, where you keep secrets chained and unnamed for those few who have the pleasure of knowing them.

Viccipiter grinned, You wish to see the shadows we cast? Her smirk crept wider, and her void crept closer. Her arm slid over Luma’s shoulders and in seconds they became half in league together. What hues had inhabited Viccipiter’s skin vanished quietly, and her face brushed against Luma’s ear. Even in the din of that tavern, her words carried the clear tone of an invitation bonded to a threat. She said, “You are not a spy, are you?”

To most, self-awareness might make that an impossible question to convincingly deny, but the larger portion of Luma’s mind had at that point become self-hypnotized into dully swimming between Viccipiter’s devilish grin and dangerous aura. What little was free from that was mostly preoccupied with a momentary fantasy that made wildly optimistic assumptions about what sort of imprisoner Viccipiter might make, which was predictably extending past the moment she had intended to allocate it. So, when Luma shook her head no, she had stars in her eyes that sold her as possessed by an innocence not even possessed by the stars in the sky, and Viccipiter did for a moment think that her own eyes might not be the most precious in the room.

A second runed arm joined its pair on her far shoulder, and the shadow mage draped over her like an obscenely expensive coat.

Luma wondered then, Do I need a cloak to fit in?

She was told, “You will never fit in. And worse, a Menemor sees through illusions as if they were not even there. But that does not mean you cannot be smuggled in.” And her face filled with an unreadable smirk.

Luma stared into the gold an inch from her, which looked like mirrors to the eye and felt the same to the soul, and she chose to ignore how much danger she was putting herself in. Or more specifically: the danger she was putting her quest in, by signing her starved heart up for a test of resistance. It was a troubling amount, but she had been at a maximum of trouble for longer than she dared to count, so the difference had difficulty adding in. She felt she could pretend this headlong fall was instead a calculated risk so long as it led to the slightest chance of any real leads. That was enough excuse for Luma to rebrand the indulgence as duty.

The shadow mage could see rationalization win its war inside her, and held open her cloak for Luma. She cautioned, “I can guarantee your entry, but not your safety, nor your exit.” But these words were lost on Luma, who had already stepped inside and disappeared from the tavern, from the city, and from the realm entirely.

Chapter 3

OVERSHADOWED

The author would like to make it clear, here in the third chapter, that we are already drunk. Drinking is a close cousin to devouring, but of lesser apocalyptic scope and therefore infamy. You may be confused by the scale, but a Devourer does not need oceans to become intoxicated. Oceans, save for their inhabitants, merely hydrate. Believe it or not a single nervous elf will do fine.

We mention this for the disclaimer, but also because our selected characters will soon make for fitting company. That may sound misplaced to you, but stories and memories are not past nor fiction to us. They exist as real as anything else exists, and when we log them, they happen in the moment. A mortal mind simulates its surroundings in order to navigate them, and its stories to hypothecate. But a Devourer’s mind is all one simulation, impossible to differentiate. Dreams as vivid as dinner.

So it is that we are with everyone as they go through their lives, even though it is not until later that we meet them and they meet our teeth. So it is that our eyes and mind are, and were, with Luma long before she entered our mouth, back when she stepped into that shadowed house.

Luma did not actually expect to enter that, or any, area, since she saw the world through her own lens of interests and so expected to find, inside Viccipiter’s cloak, a comfy fabric in which to share a romantic walk to their destination. As such, she arrived at the greeting area of the shadow house in the form of a sprawled jumble of elf on the floor, and she only wasn’t trodden upon by her smuggler for the graces of that girl’s quick reflex.

The other thing she didn’t expect was an interior that compelled her to pen a reaction such as, Oh this is lovely!

Inside the vanta cloak of Viccipiter et Menemor was a grand lobby, circular at the walls, as if filling out one floor of a turret. There was an exceptional amount of fireplaces, each harboring the ever-popular magic of undying flame. Favored not only due to its perpetual nature, but also for such a flame was incapable of spreading itself, and therefore could go unattended with no risk of devouring its caster’s refuge and any wee children dwelling within. Despite their number, the air was perfectly comfortable and welcoming. That mysterious Menemor brand, oft seen as a house of evils and occulteries, did not show itself here on the inside. Or at least, not in this immediate greeting space, which admittedly did nothing to vouch for the presumable dungeons.

It was refreshing to need not pause and aim stationary at someone in order to say the slightest thing. Luma found that she could scribble upon anything clutched in her hand, and the shadow mage would respond without looking, often before she had even finished the sentence, and without stopping what she was doing. By the time Luma had gotten her bearings, Viccipiter was idly walking atop any furniture that was not meant to be walked upon, putting her boot to vases and candles and the like. She said, “But of course. A house must guard its reputation,” as if ignorant of House Menemor’s very opposite one. And her projectiles elastically returned to their placements behind her.

Every time the mage turned her back to her, all Luma’s instincts as a natural snoop kicked in. Which was fine. Her guide was basically her accomplice, and didn’t seem to have a line of sight to avoid, anyway. Not that Luma was a stealthy snoop. More of a brazen one who never understood the issue.

So she went straight to the next-nearest doorway and brushed aside the cover draped over it, finding a normal door behind the cloth, wooden and inconspicuous. All locks were inferior to the impossible lock upon Luma, and so she would have attempted to breach the thing except that it did not challenge her identity, bite at her agency, or refuse to cooperate in any of the normal ways that were favored in magical security. Instead it opened easily. And the third layer to this scheme was a simple wall, bare and unadorned in a naked shame, as if it was never finished or even supposed to be looked at.

So she wrote, Your door is a fake.

Viccipiter jumped off the side of a staircase and brushed past Luma with the conditional affection of a housecat, sending a shiver of static, or magic, across their edges. She walked said door shut and then flicked it open again, gesturing performatively at the new location that lay beyond. A dawnish, foggy landscape of grass and scattered treepatch.

And she said, childishly, “It seems to work for me.” Which only did not work as bait to banter because it worked too well at impressing Luma, who became preoccupied with that instead.

Luma thought about what she was seeing, and she thought she had an idea, so she told the idea to Viccipiter. She wrote, It is a pocket house! And she very much thought she had cracked it.

“Nothing quite so simple.” A disappointing response, which might have led to something more satisfying if she had given time for Viccipiter to explain, rather than immediately bounding across the threshold to have a big lookaround.

The shadow mage closed the door behind them, its latch snapping into place and its cover befalling it, becoming another false doorway that led to nothing. Her voice adopted a spookish lisp as she slunk up behind her target, and she whispered, “This is the hunting grounds. We bring unsuspecting beings in here from time to time and let them loose. For practice.”

For sport? Luma had never played a single sport, but expressed herself like it was a lifelong passion. What do you hunt?

Her smuggler’s voice lowered further still, her hand on Luma’s back. “Only the most dangerous game.” Luma’s eyes widened, in shock and awe, and she looked frozen into Viccipiter’s eyes.

Monsters? she guessed. Like: big, gross monsters?

“...Yes,” said Viccipiter, not knowing what else to say. “Big, gross monsters.” She stuffed her hands back in her cloak and strolled a few steps away.

And then Luma’s hands grew quiet, and her gaze grew thoughtful. She wrote, Wait, and momentarily added, I see what you are saying. Her smuggler watched, rolling on her heels in a lost expectancy.

She wrote, We must cut through here.

“Oh?”

The inner house is moated by monsters. Because only a shadow could slip past without causing an alarm.

Viccipiter stopped biting her lip. “How sharp you are.” And she considered for a moment, before saying, “But that is not what I was getting at.”

I know, came the followup. I can see the obvious. Luma turned from her surroundings to her host and wrote, There are no monsters to be seen.

The already high eyebrows of Viccipiter shot up.

Because they are invisible! Luma rationalized wildly. It is a moat in which you sink if you rely upon sight. Because a shadow mage has no eyes.

And the aforementioned eyebrows lowered all the way down into a squint of concern. But Luma had already closed her own eyes, and so she missed this expression. She merely continued seeing unsolicited connections between everything, in the way of one who had been scouring innumerable pages of text for the slightest clues to a rare puzzle for the better part of a decade, and had forgotten that there are other ways to be.

So she wrote, I cannot see as you see. But I can hear as you see. And she forgot not to say, Maybe better. Luma became even more silent as she stuffed her stationary away, and took out her strumweave, her noisemaker. But she pressed the cords down, and held that thing tightly, like it was an antenna plugged into her hands, and her ears took on a twitch. Then she set off, across the quiet, empty grass.

As she did this, her sponsor strolled behind her, not nearly silent of foot, barely quiet of tongue, and whispered, “Does nothing escape you?” But the bard had no extra hands with which to respond. “It is no wonder you have survived traveling all over Pedesyn on your lonesome.” Luma stopped, turning this way and that before continuing. “Like, truly, I do not wonder at all.”

Viccipiter did not look for monsters, nor listen, and instead focused the entire time on Luma. It hit her, what she was trying to do. She had to say, “Bard, are you attempting to eyewander?”

A term Luma was not sure she knew, but it sounded much like her first guess, so she gave a curt nod.

The girl said, “Interesting,” again, and spoke of her own experience. “We must begin our eyewander at only a few years. Or less. You think you can pick it up on the day? With your life at stake?”

To some extent Luma resented that. She had been strumming weaves since about the same age, admittedly not as often as one used their eyes, but still. She should’ve remained an inch shy of legendarily attuned, even then.

She was asked, “Would you like a hint?” and nodded fervently enough that Viccipiter was retroactively even more bemused by her choice of strategy. “You are not doing the obviously correct thing.”

That did not seem like a hint to Luma, so she merely pouted.

Before she could decide whether to set her strumweave aside and bargain for a better hint, it was given to her for free. Viccipiter said, “You have an eyewanderer right here with you, goof.” And the obviously correct way was revealed unto Luma, who smiled in that open-mouth way that the shameless and the elves did. She stuck out her stubby little hand that had never hit anything hard except for notes, and it was clasped in a hand of prickling, electrifying magic. The blind led the bard — who still kept her eyes closed for some reason — across the cool and damp grounds.

Viccipiter wound through the invisible maze and all its puzzles and riddles as if they weren’t even real, and her path twisted for about as long as the mage’s idle thoughts could entertain themselves. She whispered when to stop and when to go, until she was bored of it, which was twice. The problem with holding hands with Luma was that she could not write, which made it a pleasant but dull affair that the clever tired of quickly. So it was that the pair beelined to the next nearest door, which may or may not have been the same one, we will not tell you and Luma did not know, for she had been focusing on her senses and had neglected her cardinals.

In her grace, Viccipiter said, “You may open your eyes. You have made it.”

And Luma marveled. She wrote hastily, What luck! I rather thought I might get eaten out here.

The only response to that which seemed appropriate to Viccipiter was, “Not... here or just yet.” But her head did not track Luma as she said it, as if she had the ability to make eye contact and therefore the ability to shy from it. Instead she occupied herself with opening the fake door, and as a reward got immediately ambushed from behind by a hug that was half a glomp and the other half a severe culture shock. She watched Luma, sightlessly, as the bard skipped cheerfully down the creaked stairs of an unlit basement.

✦ ✦ ✦

That door, when closed, revealed itself to have been the single source of light bouncing limply down those stairs, and its betrayal was met with a silent, but emphatically fonted, I cannot see!

Viccipiter cast her signature foreshadow over Luma. She said, “You are infiltrating the shadow house. It will only get darker from here.”

She was asked, by a stumbling cuteness, Can you cast a light?

Which she thought to be a humorous softball, easily bunted. “Have I, who does not perceive light, learned to cast an illuminating spell?” And there was a chuckle that came from wherever she was. Luma thought this was an answer, but it was a lie if anything, for that was a spell of such novicery that even Luma the bard might have learned it if given a middling tutor and forty-five minutes.

So Luma, who again could have just asked, bumbled around with hands outstretched until Viccipiter, realizing she was trying to follow her voice, arranged herself so as to be found. Her pockets were searched, and Luma pulled out the girl’s hands and held one. Except in this iteration of handholding it was held aloft, and used as a lantern on account of its glowing runes. With that puzzle solved, Luma snooped anew.

And Viccipiter strolled along with her, questioning how it came to be that her utility had become so antithetical to her fashion. When she voiced this, Luma rested the girl’s luminous hand on her own shoulder so that she could write an apology. She asked, Why tattoo yourself with runes that shimmer, if you are so dedicated to darkness? and was told, “Some light draws the eye. But too much light is the same as shadow, to those who have eyes to blind. So we keep a ready supply on-hand, simmering.” Luma offered to continue without it, if it truly bothered her, and for a response the shadow mage laughed at her like she couldn’t have been sincere, which she was, which was why it was funny.

“As I said,” Viccipiter’s humor always came to a rolling stop. “I do not perceive light, so light cannot trouble me.” And if Luma had looked, she would have seen her turn so voided as to be featureless, as if to prove the point. Instead her eyes caught on something much less subtle, and wrapped the girl’s hand tight around her waist so that she could fiddle with her immediate surroundings.

She wrote, There are elven wines here! Which might sound normal when you are told that they were in a wine cellar, but you should also be told that it was terribly abnormal, actually.

“And orcish.”

Why would you keep elven wines? Luma brushed them, to see the depth of their dust and the numbers underneath. These are from before elves even began sailing to Pedesyn. How do you keep elven wines here?

And in lieu of answering, Viccipiter asked, “Do you think you have found your first secret of ours?”

Already? Luma blew through her lips as she wrote, which did nothing. It would be too easy.

Her date nodded in a lulled sarcasm, and adjusted her hair. Before she could figure out the wording to an innuendo about when things would get hard, Luma whipped around, bright runes repeated in her eyes. She wrote, It is all poisoned!

Viccipiter’s face said nothing while her mouth said, “But of course. A whole wine cellar of poison, brewed for every race,” in a tone that said it already clocked out for the day, and not to call it again.

Five years ago, Luma would have caught that tone. But she was seven years into an insanity that most elves couldn’t have even survived, and so she continued, this time in the form of a question, We must drink it to proceed?

“Yes,” said Viccipiter, realizing that she needn’t have packed her creativity today. “Because shadow mages, as everyone knows, are immune to poison.” She said this because she thought it did not make sense.

But Luma made sense of it readily. What better way to convince someone to drink your poison than to drink it yourself?

Viccipiter took a bottle in her hand and pretended to look at it. Then she pretended to side-eye Luma. She said, “And you expect me to drink enough poison for two?”

The elf shook her head. No. I will drink mine. And unlike the mage, she looked at the bottle for real, with some kind of expression that only didn’t betray her thoughts on account of those thoughts being unrecognizable. I think I can take it. And then she took the wine, took her date’s hand in hers, and walked around to the far door, so that the thing could see them do this.

She needed no corkscrew. Before the mage could do any such party trick herself, Luma flicked the side of both her and Viccipiter’s bottles, sending each ringing almost as if they were already emptied, and their corks ejected themselves in rapt obedience. Her smuggler looked at her as if she had found an extra contraband in her false cargo backing. She said, “You are experienced in this?”

Luma sighed, and did not explain that she did not drink upon her quest, lest it and her life devolve in the obvious way. Instead she clacked their bottles, and locked their arms to drink in unison, as if somehow they were celebrating. This was not an elvish custom, but it was a human custom that Luma had assumed applied in any scenario.

Her sponsor’s head tilted ever so slightly. “Are you sure?”

A nod responded, one just as fierce as it was a bit lost. And Viccipiter actually had more to say, but not the time to say it before the elf began chugging a half-litre of poison. She only had the time to hurry and join, and did not at all have the experience to keep up. It seemed to her that drinking and barding must be taught in the same schools, for the elf did not even appear to swallow rather than simply pour into herself like she was emptying the thing on the side of the road. Viccipiter did not take the challenge. She took a sip, and when she was done, so was Luma, and Viccipiter expressively gagged and said, “Ew.” And upon her face was a scrunch.

But she quickly pulled herself together because it appeared from Luma’s face that the elf was choking, asphyxiating, and all-around straight-up dying. The bard fumbled for her stationary, in the way that those not long for this world wrote their last ominous warnings in blood. And her sponsor grabbed her by the arms, looking her up and down, and through, for she knew absolutely jack-all about poisons, and therefore nothing about what to do if there was some, and it got used. She hid a tangible relief when her date gasped back to life.

Without waiting to even out, Luma scribbled angers out on her pad, That was the worst wine I have ever had!

Viccipiter’s alarm converted to skepticism, and she challenged those words. “That was not disgust! You began to perish!”

I could barely choke it down!

“Your concerns are misprioritized.”

Gross!

“Did you expect poison to be smooth?”

Yes! A poison should have some grace, so that it is not vomited back in an assassin’s face! She crossed her arms, which for how they carried the former responsibilities of her mouth was a gesture of finality.

Viccipiter’s words succumbed to choice paralysis. She was left with only, “Well. you survived. Congratulations.”

Luma disclaimed, I am going to be a bit stupider soon. And upon her frame was already a wobble. Then she burped in the worst direction of straight forward. One that would have been grand were it not for the graces of her most hated accessory. Still, she covered her mouth in a hurry.

Viccipiter almost smiled at her, for some reason. Luma had only seen her smirk or grin before. The mistake was quickly corrected.

“For one with experience, you are a lightweight.”

I am no lightweight! Luma objected, even while Viccipiter took her arm. It is only that humans are all of you such heavyweights!

Instead of leading her out, Viccipiter stalled, and asked, “Do you think you should rest a few minutes.” But Luma simply repeated her earlier comment about how she never planned her rest, which was not reassuring.

“Luma. I must caution you. This is not going to go entirely the way you think.”

Then I will simply think much worse things, so that it may go well.

“Is everything a riddle, or wordplay, to you?”

If life was simple, would it be worth living through?

The mage realized then, for the first time for real, that having a bard for a girlfriend might sometimes be annoying.

So, in chivalrous fashion, she opened the door for her, and gestured at the blank nothingness within. She said, “This is our bottomless pit.”

Luma looked, as if she could see anything, and nodded, as if she had. She wrote, Cool.

Viccipiter said, “Jump in.”

And Luma jumped.

And Viccipiter whispered, “Ho-ly shit,” as the elf traveled through the air, and hit the stone floor in front of her.

To her credit, she very nearly landed it, and it was the wine that truly tipped her over. But it was a victory enough to have passed the trial, or whatever. Her sponsor strolled over, proclaiming, “If all of life was a test of conviction you would be the King of Pedesyn by now.” And she laughed at her.

Then she stopped, as if gutted, pulled her bard up and stuffed her in her cloak. Which did not send Luma sprawling to the lobby, but more floating in space, buffeted by cloth. And from the outer reaches of that space two voices faded into being.

They spoke of some business, as indecipherable as it seemed inane. Numbers and keywords, spoken in the way one speaks nonsense when they know another will understand it. They paused at finding our shadow mage standing alone and inactive in the center of that room.

Viccipiter quietly growled a mantra. “May the darkness envelop you, brother.”

One said, “And may it envelope you, sister,” but in a curious tone. And the other one, who was already walking away, only said, “Yeah. Okay Viccipiter.” When they had both passed through a presumably false door, Luma was dragged across an infinite expanse of space and placed down, on her feet, carefully.

She wrote, They sounded nice.

Viccipiter spoke the way a proverb warned. “Nice is another shadow to mask danger within.” But when that lingered without a response, she added, “But yes. One of them is nice.”

She didn’t consider that a bard would know far more proverbs than she knew, or would improvise. Luma wrote, We must let a little danger in, now and then, lest we not recognize it when it comes on its own.

“A little danger?” Viccipiter questioned Luma’s sense of moderation.

The bard had two hands holding onto her one, and was swaying gently to the lack of a tune or breeze. She was staring into Viccipiter’s surreal eyes of real gold, and there was a stupid grin upon her invincible personality.

It was then that Viccipiter decided to tell her what she had been thinking. She said, “You know, I saw you in the library many times before. Always drab, despondent, entirely unfocused on your work. After I helped you out, you smiled at me, once, and it was the smile of someone who smiles all the time. But it was only the one. It was alone like you were alone. Then I started to look for you, and I spotted you day after day, almost no matter the hour, in that drear. Studying, thoughtlessly, not seeming to absorb a word. Never again did you smile, even though you were so good at it. Until in the tavern when you realized I was flirting with you. Then you lit up like a torch, like an upcast magelight, bright as the sun. You are bright as the sun, yet you seek the dark. You did not even follow me here. You asked to come. Into a house with no windows, no candles, and no eyes. And now here you are in the thick of that, grinning in glee. Do you know how gritted I would be if I were you, and this was unfamiliar to me? I would be planning my imminent explosion.”

She peered through the beaming face of Luma, whose glee had blossomed throughout the mage’s words, taking the expression of a connoisseur or collector, finding the perfect stamp to complete themselves with. Luma’s mind was on the girl’s shimmering depth, her stalwart posture, and the subtle features of her face as they bounced the dim light softly away into the nothing that backgrounded her.

She wrote, You are so cool!

And Viccipiter said, “I think you have missed the point of the story.”

It was half a minute of dazzled staring met by suspicious squinting before Viccipiter folded. She said, “There is something else I wish to show you,” and led her back to the door they came in through, which opened to somewhere new. “Come into the dungeons.”

This time she left much more light for Luma, with both hands out of her cloak. Hundreds of shadows cut over the jagged stonelay as their source strolled through the many iron-barred rooms, flickering at the slightest change. There was a shrieking crane as she pulled open the grate of the closest one. She said, “Get in the cell,” and watched Luma’s dutiful obedience. “Put on these shackles.”

That was difficult to do on one’s own, so Viccipiter helped her with the second cuff. The bard stared up at her as she worked, thinking something unknowable. When it was ready, she tested the chain between her wrists with a few tugs.

“Right,” Viccipiter concluded. “Now, get in the torture chair.”

And Luma got in the torture chair.

She helped her shackles match up with the iron rungs on it, so that Viccipiter could flick its clamps into place. And then, that was that. Her abduction was complete and total.

So they stood there, and sat there, for a minute. The captor with her hands on her hips, and the captured staring up expectantly, as if a fan that had been summoned onto the stage.

Eventually the mage said, “I must reveal to you, Luma, what I have been hiding from you all along. I must now tell you what thoughts I have been truly having for some time now.”

Luma nodded three times.

And Viccipiter’s head listed slightly. She completed a full circle around her victim and said, “I have absolutely no idea what you think you are doing here.”

Luma did it again.

“I confess: I understand nothing about you. You realize where you have come, right? Did I not make it clear? The danger you are in? You know that an invite is no magical contract guaranteeing cozy hospitality, right? I could leave you in these shackles, here in the darkest cells of this world, where the doors lead to nowhere, an infinity away from the nearest ears that could even consider answering your pleas. Which, now that I think of it, would never hear you any which way!”

She said, “Stop nodding! This is serious. There is an intense discrepancy at play here.” Then she leaned over her mark, into her space, her voice gaining some violence. She interrogated, “How did you manage to survive seven years traveling Pedesyn alone with this complete lack of self-preservation!?” Viccipiter pulled her by her collar, beginning to laugh.

So Luma began to laugh, because Luma was nothing if she was not included.

But the laughter stopped abruptly when the door across from them opened. It opened casually, but was as loud as a carriage crash in that completely dead space. They both froze.

There was an empty moment.

After which someone new said, “...Viccipiter what are you doing?”

The perfect posture of the apprentice returned to her. She answered slowly, “I am on a date.” She said, “What does it look like I am doing?”

The new voice was deep and slow, like gravel falling over the edges of a shovel. “It looks like you have abducted some poor elf.”

“I resent that. I have never done such a thing before. And: it so happens that pretty elves follow me willingly.”

There was a hum of incomplete belief. “Is that so, elf? You are living out your own wishes here, in harsh captivity?” Then there was a bright flash, as the new Menemor cast a light that was far too bright.

Luma shriveled up her eyes as they attempted to contract at record speed. Viccipiter was unaffected and said, “She does not speak.”

The senior Menemor adjusted his magelight in accordance to Luma’s reaction. He was a tall, gritted man, of mixed skin, impeccable handsomeness, and the appropriate amount of dishevelment. He responded, “And yet you are interrogating her?”

His junior crossed her arms. “I do not expect you to understand romance.”

As he approached the cell door, Luma saw his eyes were silver, and that they narrowed upon her.

After a stalled moment he said, “She is manipulating you.” And it took Viccipiter’s shift in body language for Luma to realize that he was saying this to his own, rather than to her. “Can you not see the lies in her?”

Viccipiter looked, in her own way. “Which ones?”

And he pointed, as if they existed in places. “She has loves already, and feels she has ventured too far from home for too long. She desperately wishes to return. And, also, she is hiding her true abilities.”

“See this is what I mean about you not understanding how romance works.”

And then, the two began to speak in what was obviously code. He told her, “Are you not worried for the ancient scrolls locked in the basement?”

“Of course not. No one can steal the ancient scrolls locked in the basement. It is impossible.”

“I did not say it was possible.”

“Not even someone who traveled all of Pedesyn studying every antimagic available could do such a thing.”

He said, “But what of the larger concern?” Then, when she asked, he said, like it was obvious, “Does her deceit not cast a shadow upon your romances?”

This was given a few seconds of thought, at least. “Well not yet it has not.” She said, “It is you that is casting your shadow upon my romances, hovering like this over us.”

But apparently that was the end of the conversation. For he then said, “Regardless, I need the dungeons. This is not an area for play. Make your way.” And ironically he followed this up by leaving. Although before he was past the threshold he turned to say, “And cast your date a light, for goodness sake.”

✦ ✦ ✦

Viccipiter watched her elder go. If she was going to make her way anywhere, she wasn’t hurrying about it.

She told her victim, “Do not worry about him, he is a harmless old hoot. We only keep him around because he is insanely deadly.” She was definitely exaggerating the age of the man, which confused how the other claims should be taken.

Luma had no freedom to write, but her face said as much as it ever had. Viccipiter wasn’t sure what it was saying, only that it was expectant in some way.

She said, “What?” And when the face did not change she explained, “I am going to torture you. Wait, sorry. I am not going to torture you. There is little I could do to you that would be worse than what you have been doing to yourself. How someone chooses a life of homework is beyond me. Even if I lost everything and saw no other way, I would rather spend all my time finding that other way.” She looked at nothing when she said, “I do not understand the faintest thing about you.”

Some recreational interrogation would have been preferable. Luma knew a lot about how to squirm and strain and gasp. She knew when to resist and when to obey. But one of the worst things about being muted was that it left her with next to nothing to do when bound.

“You look great, by the way.” Her date smiled at her vulnerable state, and her humor worked on Luma, which she liked, because it didn’t work on most. “Although I suppose you do not look comfortable.” Viccipiter then set about releasing her. And Luma, having spent many years working towards conquering the impossible lock around her neck, did the gracious thing and let her be the one to do it.

When Luma was up, and had her words back in hand, she wrote, He seemed nice, too. And, Are most shadow mages friendly like you?

“My people are, for better or worse, composed of people.”

This time, the girl’s face stayed on Luma, and she followed with the question, “Well? You have been found out as an aspiring thief. Just how foolhardy do you intend to be now?”

Luma wrote, I have never been a thief. Not yet.

“That is wise.” Viccipiter shrugged, and led her out of those dungeons by the wrist. “It is much better to wait for the right opportunity, and so only need to do it once.”

I do not actually want to steal anything, nor expose any secrets. The instant I find my freedom I will close my book on this chapter and never think about magic ever again.

“Ha!” This aspiration summoned a laugh. “You will never escape magics in this life. The same as, if you ran right now, no matter how fast, you would not be able to escape me.”

For a moment, Luma stood in the darkness again, listening to the fluttering pages of Viccipiter’s personal tome. In that awkward length of time, the mage explained, “Hold on. I have only practiced this for combat.” There was a flash, and a pat on her head as the light was placed over her, tied to her location and offset somewhat up.

After two-dozen blinks, three stumbles, and passing through one doorway, Luma found herself in the entrance of a lavish speaking hall, with a floor that was stepped at every part, mirroring a ceiling that looked as if it took the form for acoustic reasons. And more striking than that, it was busy. At least two dozen Menemors were making it their space, most with their tomes out, sharing or discussing business, far fewer sounding like they discussed magic.

Luma had the very distinct feeling of shining a conic lantern into a cave of undisturbed bats, and being voyeuristically alien, particularly for how cold and harsh her light was. It was only a few that noticed the light at all, and they seemed wholly uninterested in the intruder after a second’s distraction.

Pedesyn held many conflicting rumors as to which shadows the Menemors crawled out from, and Luma realized instantly why, for each was about as right as it was wrong. She herself was not even the only inhuman, as there were two orcs in the forum when it wasn’t even in session, and perhaps the most surprising thing was that they were not together. She spied an elf, too rich of skin to be any kin to her, and the bulk of the humans were from every cardinal on the map.

Viccipiter told her, “This is our forum. Emergencies and governance.” Luma only realized then that she was being given a real, actual tour. Her guide mistook the realization for confusion, and so gave a more candid explanation. “This is where we decide who lives and who dies. Or: which laws to respect.”

Luma started to write, but her ink was jostled into a scribble by a horde of little gremlins (see: children) that knocked into her along their run. Two of the gaggle wore blindfolds, and when they lost their balance they took another two down with them. All of them carried instruments, and so as they engaged in a floored scuffle it was set to a discordant concert, and Viccipiter laughed at it. Those who first bonked upon Luma apologized to her as they rose, in the broken language of those early in learning to speak, which was enviously more than Luma could do.

Viccipiter kept one hand on the door handle and asked, “Where are you headed?”

One said, “To the library.” And was quickly cut off (and in front of) by another who said, “To the pantry!”

So Viccipiter chose to believe the latter. She waved her hand over the door before opening it, as if spellcasting was a show to be put on, and then ushered them through, with a bid that they have a good day. She was thanked, politely, and the manners of the children stayed mostly intact until they were well into their destination. It was only as the door swung closed that Luma heard pitched squeals and the raiding of foodstuffs.

There was also an elder that passed them and went through. And then quickly returned, looked to Viccipiter and said, “Viccipiter, really. Where did you send my class?” Viccipiter told her the truth, and this wasn’t appreciated. She was told that she knew better than that.

Viccipiter played dumb. “Who am I to detect lies and accuse liars?”

“You are the perfect person to do that on account of your familiarity.” The squinted silver then noted Luma for a second, and whatever was thought of her, it wasn’t to be known, for she said, “I won’t even ask,” and then continued on to the pantry.

When her guide next opened a door it was to a lush garden, tightly packed with exotic flora growing over every surface and none respecting any others’ space. Luma looked at some part of it, was amazed, and then looked past that and repeated the process many times as she came to the greater realization that this garden was more of a landscape. It continued until it formed a horizon, in the way land did, but without the repetition or uniformity. An unabashedly artistic scene, but one whose artist had tripped and spilled their palette across it during an over-acted multi-stage fall.

Viccipiter held her wrist as they walked through, even though there was light enough for Luma to feel steady, since there were plants that needed even greater quantities of it. “This is, globally speaking, the most complete collection of plantstuff in existence.” She grinned then, as if proud to have contributed, which she hadn’t. “We have not inspected other houses’ gardens to compare, but seeing as ours is literally and actually complete, it has to be.”

And Luma was not listening, having been overcome by the need to point excitedly at a flowery vine that grew across her childhood town back on the opposite side of the world, which she had not seen in the better part of three decades and had expected to never see again. Viccipiter did the thieving for Luma, plucked some and slid them into her girl’s hair. There had been many years as a child when Luma had not gone a day without flowers in her hair, but at that time it might have been close to a decade of the opposite. Instead of telling her, Viccipiter asked, “Is it your color?”

She wrote, Any color in the wild is an elf’s. Her quill tapped on the paper twice, before asking, Are you colorblind? Which might have been a rude thing to suddenly ask if not from the muted.

“No, but I do not see things the way you do. I can read a color. I cannot judge it so well.” She puffed out her cloak. “Thus the black.” And she thumbed her cheek.

Luma smiled and wrote the truth. I love your style. It fits you perfectly.

“I like your mind. It confuses me.”

Now that I can see, this is all so lovely. Luma rhymed her, as if that would mask her abrupt change of subject. She walked through the grassway, brushing all the plantlife with her hand, as was the elven way.

And Viccipiter bapped her arm, “Stop touching everything, or you will eventually be poisoned.”

But this place is all so pretty, and cozy. What is worth fearing here? I can take another poison.

“A real poison, pretty one.” Viccipiter eyed her for effect, trying to gauge whether she was pretending to not know that they were pretending before. She sighed and said, “Well, we see differently. This looks to me like the most dangerous place. It looks absolutely laced with traps.”

Traps?

The mage only shrugged. “The endless threat of comforts. The imminent doom of peace and quiet. The tedious boredom of a life lived correctly, safe in the shadows.”

Oh. Luma did, actually, know exactly what she meant. I came across the great ocean for reasons such as this. She left out the part where she also just really had a thing for humans.

The sights of the garden held Viccipiter’s fickle attention no better than you’d expect, and soon she backtracked them to a thick tree, and put her hand upon a gnarled door that had not been there as they had passed before. She said, “Where are you headed?”

And Luma thought about it a lot less than Viccipiter expected her to. She immediately wrote, The basement with the ancient scrolls?

“I admire your boldness, but that was not a real thing either.” She smirked. “Try again.”

Your library!

“Ugh.” The mage squinted at the fool, but acquiesced, and Luma scuttered into the tree with the giddy humor of one who knew they were being spoiled.

A taller library there had never been, for there was literally no reason to design a cataloging system to run so harshly vertical. The bookshelves only started to hold books at about the height of her own head, and it couldn’t be known how high they ran because the light she wore for a hat gave up the chase at about five-hundred feet. Each was a solid and single piece, as if the library was a redwood forest seeded at the beginning of the world, and there was a dampness to the air that conflicted with the proper means of paper storage.

Viccipiter continued her tour by illuminating, in royal sarcasm, “Nerd shit.” She dropped her tone, “You... cannot sleep here,” and was about to inform the bard that she would be welcome to sleep in the next room, but hadn’t the time before Luma had skipped inside and started browsing in expectant awe.

The very first text she set her eyes upon whispered to her. She heard it in her head like a schizophrenic, a growling voice just inside her skull, reminding her in which season did reindeer mate. As she vaulted up the first shelf to listen closer, a scroll affixed above that one told her, with what she intuitively knew to be a personal importance, how to tessellate pentagonal bricks. This attempted to happen a third time but Viccipiter interrupted with a request for the far more pertinent knowledge of what the fuck she was doing.

It was only natural for an elf to climb a tree, but Luma did not have the hands or voice to respond naturally, so she simply looked down. Then she saw that Viccipiter had asked for a friend, as joining her was a presumable elder, who looked like a nun (despite wearing the same cloak as the much cooler one beside her). She looked at Luma like she was stupid, and looked at Viccipiter like she was the one climbing the walls.

She said, “And who is this?”

“That is Luma. She is my new and adorable sidekick elf.”

Luma didn’t know the proper custom and, as her wit had always been words and therefore had left her, she had since learned that everyone can appreciate a polite little bow. But she couldn’t do that right then, so she just stared.

The woman said, “Well, take her back to her forest. She is a trespasser in this house, amongst our secrets. If you wish to date you should do it outside, in the sun and the noise.”

“We wished to date in here, amongst the secrets.” Viccipiter said this like it changed anything.

“Then you should have kept your date a better secret. Take her out of here and take her out properly, for iced cream or the petting of animals, or whatever our accursed children do now.”

✦ ✦ ✦

The two wound up outside, in a regular landscape, placed atop a regular hill, as the remaining sunglow sputtered its way past the horizon. A landscape bereft of the peculiarities that adorned everything Luma had just toured, save for her and her date. This put Luma on her home turf, as she had always been ready to find beauty to cheer or cry over even in the most mundane of places, so long as there was good company kept there. And the truth was that Luma found this company to be already wormed into her sensibilities. Luma may have let herself go too far and drink too deep, possibly literally.

After all that spirit-killing dedication to her quest, the endless focus, the willpower to press her tired and tearless eyes against the sandpaper of endless study, she found herself next to what she knew could easily be turned into sixty years of cherished dedication, and she wanted it. She missed being found curious and entertaining, and going about life in league with a teammate. Her imagination betrayed her with wishful images of a cozy life entrenched in the confident grasp of expert magics. She could feel her quest threatened, her fast breaking, and her hibernation waning. And a voice deep inside her said, You have to run, or you will die here. The Luma that set out to make herself whole again would be no more, that precious little thing. And Luma the girlfriend of a shadow mage would be born in her place. A happy pet failure that had forgotten the faces of her past. A simple little thing. Her potential squandered on both sides.

Then she looked at Viccipiter and a voice much clearer and closer to her surface said, Ohhh she is so handsome! And dying didn’t sound that bad so long as she got to die in those eyes.

There had been so many moments that would have been perfectly appropriate to start running that evening. But then, when Luma was finally truly considering it, the threat splayed out on the grass and stared silently at the sky. And it really would have been intolerably rude to book it at full speed right then, Luma told herself. So she sat next to her, just for a minute.

A minute passed and Viccipiter didn’t say anything, so Luma felt allowed to kill the silence in her own way. She wrote, The stars are out tonight. I feel I have not seen the stars in months.

The mage said, slowly, “Tell me about it.”

Well, I have kept so busy, and kept my head low...

“No I mean, tell me about the stars,” Viccipiter corrected. “I have not seen them in actual forever. They are too far for eyewander.”

As Luma began to write, her date added, “I already know what they look like. I want to know what it feels like to stare at them.”

A call for poetry wasn’t something Luma could parry right then. And Viccipiter seemed so still in that moment, that Luma even did the courtesy of foregoing verse. She wrote, It feels belittling. In an easy way, that belittles your problems alike. The stars say, ‘You may be small, but your problems, they are also small. You are all so small, to us.’ And you remember that everyone dies before they’re done.

Viccipiter really liked that, but she didn’t say it. She pointed her head at Luma’s strumweave and said, “Were you any good?”

Luma didn’t say.

“Were you a star?”

She nodded.

“I do not believe you.” The mage shrugged easily. “I do not think you were a star. I can see your soul, you know. It is a forest fire. A star sits in the gallery in the sky, I am told. A sun blots out the stars and causes the day, I am told. You seem more like a sun, to me.” And that was really some kind of poetry of its own.

Something you must know about Luma’s search is that finding its solution meant nothing to her. Finding its end was all that mattered. She did not care about winning, or learning anything, or defeating any ancient evils. If there was any way to fail her quest that would return her to her previous life and capacity she would have failed in a heartbeat, on any day. If anything, she yearned for that failure. How much harm could it be to make this night a bit easier to stomach? It would only mean as much as death.

Luma wasn’t one to yearn for death, for the sweet grace and mercy of the void. But she desperately missed the warm beds of friends, and so she very much yearned for the void that was Viccipiter. A bottomless pit of magical attention. The night had reminded her what it was to be with someone.

Luma’s hands were on her knees. They were steady, but she felt as if they trembled, not as the nervous do, but as those burdened for too long begin to tremble shortly before they collapse. She felt as if she had been cheated for a long time, and just now had the idea to stand up for herself and demand better.

Better laid next to her, and there were galaxies reflected in those mirror eyes. They looked like stilled pools, and Luma swore that if she leaned forward enough for her balance to leave her, she would plop right through, and they would swallow her under a tidy golden ripple. Falling had never called her name louder.

Luma leaned in, to the most danger she had even been in, and she could do nothing to save herself. It was hopeless, she had lost to this mage and to herself, so she did the only thing that made sense in that nonsense, and snuck in for the kiss.

Just as she did so, Viccipiter instinctively sat up, said something about the weather, the hour, and apologized for keeping her. She wished her studies to go well.